| |

|

EVA SVANKMAJEROVÁ: "Emancipating oneself from illusions"

by Sharon Cheslow

February 2016

(a slightly edited version of this appears in Bull Tongue Review #5)

“Every day we are subjected to some sort of test. Above all in courage. Think – I’ll tell you. Something mysterious in the stomach. They won’t pull out your tooth and they won’t take out your appendix. I will heal the secret thing in your soul, that you have under your waist.”

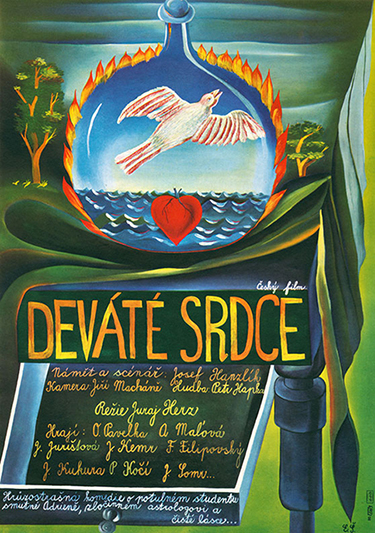

cropped still from Deváté Srdce (The Ninth Heart) opening animated credits

dir. by Juraj Herz, 1978 - painting by Eva Svankmajerová

Czech artist/writer Eva Svankmajerová (1940-2005) may not be as well known as her filmmaker/animator husband Jan Svankmajer, with whom she collaborated on many films as artist/designer, but her work is just as enthralling. Spanning forty years, her creative practice encompassed paintings, film posters, sculptures, ceramics, puppetry, animations, poetry, short stories, dream journals, and creative non-fiction. In addition to working with Jan, she also collaborated with other Czech directors (Juraj Herz, Vera Chytilová, Jiri Brdecka), and participated with Czech Surrealist Group members in collective game activities. Eva’s art and writing have a beautiful, dark, surreal, humorous style, placing haunting images of people or animals within dreamlike landscapes. In her paintings and film posters, she layers shades of colors in a vibrant style that seethes or soothes. Sometimes both at the same time. Her style harkens back to 1930s Czech Surrealist Group co-founder Toyen, with a hint of Polish artist/designer Jan Lenica. Eva’s gorgeous posters are especially distinctive through her use of hand lettering. I first found out about her in the 1990s, when Czech film, art, and writing gained a wider audience after independence from the Soviet Union. Recently I’ve been exploring the range of Eva’s incredible creative work and her background in Prague. Czech artist/writer Eva Svankmajerová (1940-2005) may not be as well known as her filmmaker/animator husband Jan Svankmajer, with whom she collaborated on many films as artist/designer, but her work is just as enthralling. Spanning forty years, her creative practice encompassed paintings, film posters, sculptures, ceramics, puppetry, animations, poetry, short stories, dream journals, and creative non-fiction. In addition to working with Jan, she also collaborated with other Czech directors (Juraj Herz, Vera Chytilová, Jiri Brdecka), and participated with Czech Surrealist Group members in collective game activities. Eva’s art and writing have a beautiful, dark, surreal, humorous style, placing haunting images of people or animals within dreamlike landscapes. In her paintings and film posters, she layers shades of colors in a vibrant style that seethes or soothes. Sometimes both at the same time. Her style harkens back to 1930s Czech Surrealist Group co-founder Toyen, with a hint of Polish artist/designer Jan Lenica. Eva’s gorgeous posters are especially distinctive through her use of hand lettering. I first found out about her in the 1990s, when Czech film, art, and writing gained a wider audience after independence from the Soviet Union. Recently I’ve been exploring the range of Eva’s incredible creative work and her background in Prague.

[above: film poster by Eva Svankmajerová for Něco z Alenky (Alice) dir. by Jan Svankmajer, 1988]

Baradla Cave

It has been very difficult viewing publications with her art and writing, since most were published by Czech small presses and are out of print. I hunted down the English translation of her novel Jeskyne Baradla (Baradla Cave), and discovered it’s now available for over $100 due to its rarity. And that’s a shame, because Eva and other Czech Surrealists were more interested in creativity itself than in the “mere artifact.” Eva lived during a time when creativity itself was a means of survival of the psyche and of community. Originally published in 1981 as a samizdat text, i.e.-self-published/distributed in the underground to avoid censorship, Baradla Cave was reprinted in an issue of the Czech Surrealist Group’s journal Analogon in 1995, and translated in 2000. Eva and Jan illustrated it. I contacted the Czech publisher Twisted Spoon Press, since their website says a reprint is forthcoming, and they said they hope to do a reprint in 2016. Yay! For now they provide a free except online. It’s a good glimpse into Eva’s use of analogy and metaphor, highly prized by the Czech Surrealist Group as means of free expression and political resistance against the totalitarian Soviet regime in Czechoslovakia. Eva compares a cave to a woman. But she does so in a way that the cave sometimes IS the woman and vice versa. She intended the story as her “poetical reflection of the earth.” Nicknamed “Optimistic Cave,” Baradla Cave has separate regions, with corridors both dark and light. It is full of “subterranean secrets.” A Map named Milada, left in the cave by explorers, is the grown up girl self of the woman. “The Map doesn’t know if she’s been bugged, and by whom.” Outside the Cave is a society damaged by biased news, materialism, and evacuated villages. The “subterranean systems” seek to liberate the world to which they connect. Her stream-of-consciousness satirical writing is riveting, and I can’t wait for the reprint. It has been very difficult viewing publications with her art and writing, since most were published by Czech small presses and are out of print. I hunted down the English translation of her novel Jeskyne Baradla (Baradla Cave), and discovered it’s now available for over $100 due to its rarity. And that’s a shame, because Eva and other Czech Surrealists were more interested in creativity itself than in the “mere artifact.” Eva lived during a time when creativity itself was a means of survival of the psyche and of community. Originally published in 1981 as a samizdat text, i.e.-self-published/distributed in the underground to avoid censorship, Baradla Cave was reprinted in an issue of the Czech Surrealist Group’s journal Analogon in 1995, and translated in 2000. Eva and Jan illustrated it. I contacted the Czech publisher Twisted Spoon Press, since their website says a reprint is forthcoming, and they said they hope to do a reprint in 2016. Yay! For now they provide a free except online. It’s a good glimpse into Eva’s use of analogy and metaphor, highly prized by the Czech Surrealist Group as means of free expression and political resistance against the totalitarian Soviet regime in Czechoslovakia. Eva compares a cave to a woman. But she does so in a way that the cave sometimes IS the woman and vice versa. She intended the story as her “poetical reflection of the earth.” Nicknamed “Optimistic Cave,” Baradla Cave has separate regions, with corridors both dark and light. It is full of “subterranean secrets.” A Map named Milada, left in the cave by explorers, is the grown up girl self of the woman. “The Map doesn’t know if she’s been bugged, and by whom.” Outside the Cave is a society damaged by biased news, materialism, and evacuated villages. The “subterranean systems” seek to liberate the world to which they connect. Her stream-of-consciousness satirical writing is riveting, and I can’t wait for the reprint.

Anima Animus Animation

I was extremely happy to recently see a copy of the Czech exhibition catalog Anima Animus Animation: Between Film and Free Expression (1998), which I got through interlibrary loan. It’s amazing. The excellent monograph documents and explores the interdisciplinary creative work of Eva and Jan, individually and collaboratively – as well as discussing the Czech Surrealist Group’s activities. Eva’s work is alluring in its focus on the transformation of self, of form, of nature, and of society. The book includes many of Eva’s paintings from the 1960s to 1990s, going all the way back to her late ‘60s painting series Emancipation Cycle. Her desire was to free herself in order to become a creative woman, transforming domestic labor into creative epiphanies. The full color reproductions of her paintings are stunning. Surprisingly the book doesn’t include her many film posters. Eva did art direction and posters for all Jan’s feature films. I was extremely happy to recently see a copy of the Czech exhibition catalog Anima Animus Animation: Between Film and Free Expression (1998), which I got through interlibrary loan. It’s amazing. The excellent monograph documents and explores the interdisciplinary creative work of Eva and Jan, individually and collaboratively – as well as discussing the Czech Surrealist Group’s activities. Eva’s work is alluring in its focus on the transformation of self, of form, of nature, and of society. The book includes many of Eva’s paintings from the 1960s to 1990s, going all the way back to her late ‘60s painting series Emancipation Cycle. Her desire was to free herself in order to become a creative woman, transforming domestic labor into creative epiphanies. The full color reproductions of her paintings are stunning. Surprisingly the book doesn’t include her many film posters. Eva did art direction and posters for all Jan’s feature films.

Eva Svankmajerová's paintings

below left: Bed, 1976

below right: A Lady's Problems, 1977

below: Vanitas - Curtain Call, 1993 |

|

|

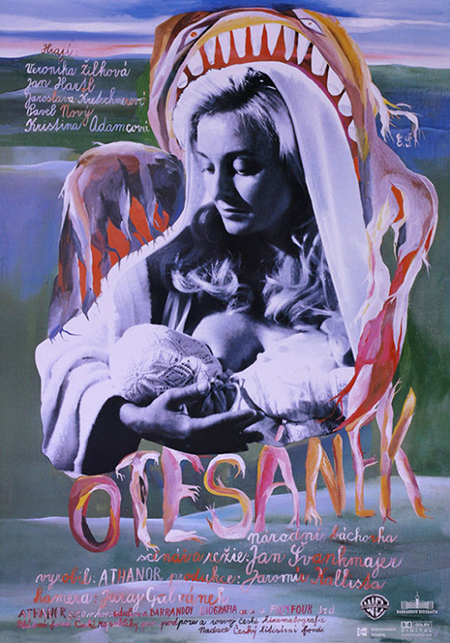

You may have seen Eva’s production design, puppetry, or art for Jan’s films without realizing it. Most notably, she did the production design and some puppetry for Alice (1988), and painted sets for Faust (1994). You can see Eva’s March Hare puppet in Alice in all its bizarre glory. In 2000 she was awarded two Czech Lion Awards for her production design and film poster for Little Otik. But way before that, starting in the mid-1960s, she worked on some of Jan’s shorts as a production/costume designer, including The Last Trick (1964), A Game with Stones (1965, under her maiden name Eva Dvoráková), and The Garden (1968). She did set design for The Pendulum, the Pit and Hope (1983), and created/painted the terrifying moving object of flaming creatures and wailing people with puppet joints – a kinetic sculpture from hell.

Eva Svankmajerová for films dir. by Jan Svankmajer

below top: set design from The Pendulum, the Pit and Hope, 1983

below middle: March Hare puppet from Alice, 1988

below bottom: film poster for Otesánek (Little Otik), 2000

In addition to her work for Jan’s films, she also did paintings for Jiri Brdecka's Jsouc Na Rece Mlynár Jeden (A Miller Lived By a River, 1971), and the painted animation and film poster for Juraj Herz’s Deváté Srdce (The Ninth Heart, 1978).

The latter features an amazing opening animated sequence credited to Eva and Jan, with painting and script hand lettering clearly by Eva. On the surface, the opening credits utilize animated imagery connected to Herz’s gothic horror/fantasy film – a heart and skeletons. But looking deeper, the animation seems to convey a message – that a broken heart can heal with the help of life/nature, despite efforts by dark forces to clamp that spirit in inescapable containers or competitive fights. It’s important to keep in mind Eva and Jan collaborated on this animation during the years Jan was banned by the censors from making his own films. Herz, an old friend of Eva and Jan’s, had acted in Jan’s live action/animated short The Flat (1968) – notable also for the music composed by longtime Svankmajer collaborator Zdenek Liska. Liska composed music for many Czech directors, including Juraj Herz and Vera Chytilová.

Prague Spring/Aftermath

To put Eva Svankmajerová’s creative work into context, it’s important to mention Prague Spring. That pivotal, inspiring season of liberation in 1968 was an influence on many. For twenty years after WWII, the Soviet Union applied strict policies on acceptable creative work, and banned many. Central/Eastern Europeans had to deal with not only recovering from the Holocaust, but also totalitarian Soviet rule. In early 1968, partly due to massive protests (similar to those in other parts of the world), reforms were made in Czechoslovakia – thus the peak of the Czech New Wave! Prague Spring only lasted until August 1968, when the Soviet Union invaded and regained control of the region/people. But while it lasted, it had great emancipatory and creative power. For example, the Plastic People of the Universe formed right after the invasion, having been inspired by Prague Spring.

I can’t remember when I first heard the phrase “Prague Spring,” but I discovered Czech film in the early 1980s after buying a used copy of New Cinema in Eastern Europe. It was originally published in Great Britain in 1971. I still have it. Chapters are divided by country, with lots of stills. The Czechoslovakia chapter explains, “Since 1968 only a few new films from Czechoslovakia have been shown abroad…More films were banned in Czechoslovakia in 1969-70 than in all the preceding years since the war.” Jan Svankmajer’s films aren’t in the book at all, presumably because they weren’t known in the UK at that time. It was during and after Prague Spring that Eva and Jan met other kindred spirits. They joined the Czech Surrealist Group in 1970 and contributed to Analogon, first published in 1969. Despite subsequent years of censorship, during which Jan was banned from filmmaking for seven years in the 1970s, Eva continued to create and collaborate. Vera Chytilová (never officially in the Czech Surrealist Group) was banned for eight years after Fruit of Paradise (1970) – Eva created the film poster and titles. It wasn’t until the Velvet Revolution of 1989 restored democracy in Czechoslovakia, and the region was split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia in 1993 after the end of Soviet rule, that many Czechs felt free from harassment.

Eva Svankmajerová's film poster for Vera Chytilová's Fruit of Paradise, 1970

Most of Eva’s creative work represented her inner life, as it pertained to life in a society that restricted her freedom as a human being. She used black humor and dreamlike images to seek emancipation from all that restricted her – including her identity as a woman and Czech Surrealist. She was part of the underground creative resistance against oppressive Soviet rule, and continued to use creativity as her guiding force toward individuation in life until her death. Her poem “Stunned by Freedom,” which appears in both Anima Animus Animation and Surrealist Women: An International Anthology, was translated two different ways, each evoking the shock that sometimes comes with liberation via creative blazes. 1 – “Stunned by freedom. You find that: a line can grab hold of you like the flight like fire.” 2 – “Stunned by freedom. To learn that: a line can thrill you like the flight of fire.” The lines in writing, the lines of a painting, the lines surrounding boundaries. Eva Svankmajerová is someone who needs wider exposure outside the Czech Republic, so her fire can spread.

|